“To grasp cell phone culture, we need to understand not only the relationships between society and culture, as highlighted by du Gay et al., but also how these relate to another important concept, technology.” – Goggin

Hello all! This blog post is about cell phone movies… or, more specifically, why I think that we shouldn’t be stressing the fact that they are shot on cellular devices or even bother calling them “cellular” anymore. So, what brought this on… well, I upgraded my cellular phone last night and during my time before bed I found myself toying with the new features, apps and testing out the phone’s camera and other hardware. I was thinking that most smart phones and tablets have become fairly advanced in their technology and have become pocket or mobile computers/media systems. This phone shoots video in 1080p @ 60fps, has an 8 MegaPixel camera, has slow motion capabilities and apps that can edit my video to my heart’s content. I can download music and add it to my film as a soundtrack. I can make my own music and score my own digital videos as well. Heck, some of these phones have enough space to hold multiple FULL HD movies. I have been mulling over our conversation in class about “cellular” or “mobile” cinema and am beginning to think that there was definitely a point in time where this prefix was necessary or inseparable from the actual work but that is no longer the case. This is due to the fact that “cellular” was part of the work’s nature by definition and tied to the experience of viewing the film. The films meant to be shown on smaller cellular screens or shot on devices that created a specific visual style (purposely low quality, etc.)

Nowadays, on the other hand, these devices are just as good as some of the digital cameras used a decade ago! Heck, even a few years ago! After thinking about the film “Tangerine” more, I really couldn’t see how the film is necessarily “cellular” and needed to be put in it’s own special category. For all intents and purposes, this is a feature length digital film. It is no different from most digital films besides the fact that it was shot with three iPhone 5s cameras. Yet, we don’t distinguish digital films by what company or model the camera used on set is unless it is fundamental to our understanding or experience of viewing the film. This is the case with films that market themselves as or intend to showcase the boundaries or advances in certain technologies (i.e. IMAX, etc.) So, it is cool to know that the film was shot on iPhones… but it isn’t crucial to our experience of the film. It may enhance our viewing but it isn’t NECESSARY to understanding the work.

Check out the trailer for “Tangerine”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ALSwWTb88ZU

Ultimately, this is why I believe that the term “cellular” or “mobile” film is just a ploy, a call for attention. It is no longer hard to make a film on your phone. Sure, it takes time, but so does filming a film on any other digital camera. It has become a useless prefix unless the film itself necessarily needs to be understood as a “cellular film” because it says something about the film. Even then, the film becomes as much of an advertisement for the technology as it is an artistic work but it is not necessary to our experience. Note the video “DOT”, which is meant to showcase the abilities of the Nokia N8, and the making of video as well as the final shots of the “DOT” short shown in class where we see the apparatus used to make the stop motion film. But, if this was not made clear to you, would you ever need to even think about it? Probably not.

“DOT” can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CD7eagLl5c4 and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XTbzSiwbRfg

So much content is shot on cell/mobile phones these days that people are beginning to not care or even think about specifying the medium. Certain types of videos are implied to be done on a cell phone such as Vines or other app related shorts.

Proof… DAMN DANIEL – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PnI-byHtMN0

People don’t care and I would argue that people shouldn’t care as cellular videos are becoming as common as any other digital short. It is no longer required that the viewer understand that a film is necessarily CELLULAR due to the advances in technology and evolution of the cell/mobile phone video in common, everyday culture… So, let’s drop the prefix?

Work Cited:

Goggin, Gerard. “Introduction: What Do You Mean ‘Cell Phone Culture’?” Cell Phone Culture: Mobile Technology in Everyday Life. London: Routledge, 2006. N. pag. Web.

A few weeks back I heard about a new video game on a podcast that was unlike any game I have ever heard of, and to say the least I was intrigued. If you are interested there is a link to the podcast

A few weeks back I heard about a new video game on a podcast that was unlike any game I have ever heard of, and to say the least I was intrigued. If you are interested there is a link to the podcast

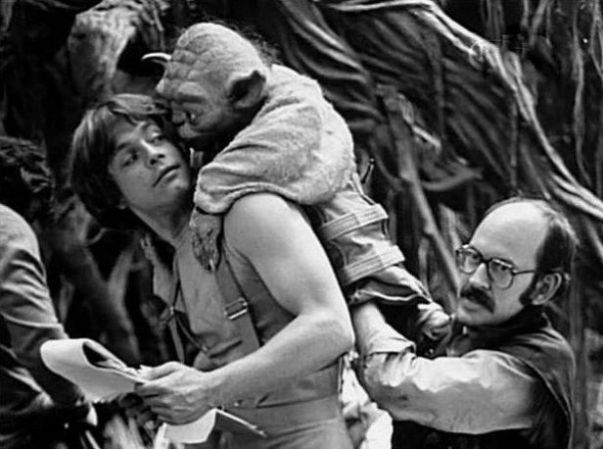

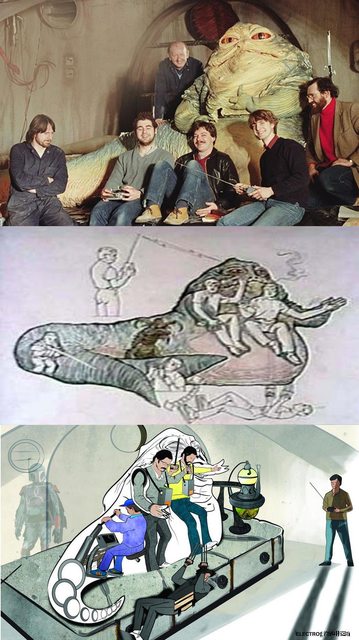

Multiple skilled puppeteers were hidden within the Jabba suit and used a complicated system of both animatronic technology and classical puppeteering skills.Without the men pictured above, and the incredible technique and skill that these masters utilized, the original Jabba would not have been remotely possible. However, animating over this negates all of the work that they put into this making their hard work redundant in the over all scheme of the film. Those responsible for the creation of Jabba and Yoda’s puppet characters would go on to create the Jim Henson Creature Shop, responsible for films such as The Labyrinth and Dark Crystal; there is no denying their skills are among the best. Yet Lucas still chose to animate over them for the Special Edition.

Multiple skilled puppeteers were hidden within the Jabba suit and used a complicated system of both animatronic technology and classical puppeteering skills.Without the men pictured above, and the incredible technique and skill that these masters utilized, the original Jabba would not have been remotely possible. However, animating over this negates all of the work that they put into this making their hard work redundant in the over all scheme of the film. Those responsible for the creation of Jabba and Yoda’s puppet characters would go on to create the Jim Henson Creature Shop, responsible for films such as The Labyrinth and Dark Crystal; there is no denying their skills are among the best. Yet Lucas still chose to animate over them for the Special Edition.

Dragon’s Lair was a great game. For its time it was revolutionary and expanded what video games could have been and helped develop what we know of them today. The game was created by animator Don Bluth and featured a main protagonist named Dirk the Dashing, who’s main goal was to enter the castle and save Princess Daphne, winning her heart and the throne to the kingdom, all in one fell swoop. The game featured magnificent 2D animated scenes, created using the traditional cel animation techniques. The animation was then used to create the video game, where the main game mechanic was fast, quick-time events, used to rid children of their hard earned quarters.

Dragon’s Lair was a great game. For its time it was revolutionary and expanded what video games could have been and helped develop what we know of them today. The game was created by animator Don Bluth and featured a main protagonist named Dirk the Dashing, who’s main goal was to enter the castle and save Princess Daphne, winning her heart and the throne to the kingdom, all in one fell swoop. The game featured magnificent 2D animated scenes, created using the traditional cel animation techniques. The animation was then used to create the video game, where the main game mechanic was fast, quick-time events, used to rid children of their hard earned quarters.

You must be logged in to post a comment.